We played a game called Suicide, never agreeing on rules due to a reluctance to write them down. On the gameboard, a series of paths branched off the edges, over the cliff. The dice, of course, were loaded. She’d been thinking about suicide so long that its hair turned white. Her own hair, red as blood, wild, rushing. Suicide or birth control—she was always prepared. I kept landing on lose one turn with both disappointment and relief. She landed on get stomach pumped once, but the second time she upended the board entirely. Her suicide mix-tape was a sick work of art, unspooling with her final breaths in that car with the hose carefully duct-taped. She was in the driver’s seat. God was not her co-pilot. Neither was I, hundreds of miles away in time and space, having shredded the map that once took me to her door. Her car was bandaged with political stickers. Mine had one, on the glovebox: Know When to Say When. We once played bingo with a group of old ladies in a church basement. I’d never seen her happier, surrounded by women she instantly loved and never wanted to become. She laughed and smoked and kidded around. The woman beside her had to point out that she’d won.

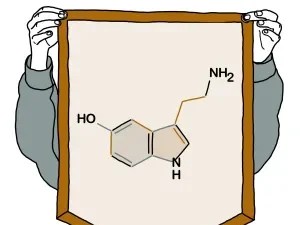

Jim Daniels’ first book of nonfiction, Ignorance of Trees, is forthcoming from Cornerstone Press later this year. His latest fiction book, The Luck of the Fall, was published by Michigan State University Press. His new chapbook of poems, Ars Poetica Chemistra, was just published by WPA Press. A native of Detroit, he currently lives in Pittsburgh and teaches in the Alma College low-residency MFA program.